Ananya Gupta and her family wore masks years before the COVID-19 pandemic began. Air pollution has made life for the 19 million people in India’s capital region of Delhi deadly.

“The concept of masks started after the pandemic of 2020 the COVID-19 virus, but in India, especially in Delhi, Delhi NCR (National Capital Region) in northern India, we have been wearing masks from 2017,” she said.

Gupta said while many people always talk about worsening air pollution in New Delhi, no one talks about the surrounding regions like Faridabad, India, where air quality is even poorer than the capital city.

New Delhi and the surrounding NCR, including the cities of Faridabad, Ghaziabad, and Noida, are the most affected because of air pollution.

The air quality index, on most days, stays above 200, a very unhealthy level, according to the World Health Organization’s air quality standards. The air quality index tracks the levels of particulates and ozone in the air and good air quality is between zero and 50.

The air quality gets worse during winter, especially during the season of Diwali, one of the important festivals for Hindus.

The air quality index in these regions often rises above 500, which is extremely hazardous according to the U.S. and WHO’s air quality index. And 35 Indian cities are among the top 50 cities with the worst air pollution, with New Delhi in fourth.

Vishakha Kapadia, a respiratory disease specialist, based in Ahmedabad, some 900 kilometres southwest of the capital New Delhi, said pollution-related illnesses are appearing in her city.

She said Non-Resident Indians (NRI), termed for people working and living abroad by the Indian Ministry of External Affairs, face the greatest brunt.

The NRIs mostly come to spend time during December in India. During that time, they face issues like Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) because of high pollution levels.

Kapadia said common symptoms of COPD include intense coughing, difficulty breathing, nose bleeding, and vomiting. It also affects people in terms of mental health-related problems, including fatigue, mood swings, and sleep disorders.

She said patients affected by pollution are seen by her during fall and early winter.

One thing she noticed among her patients is that they try to care for themselves rather than consult a doctor. By the time they reach a pulmonologist like her, it is often too late.

Gupta, 25, lives with her family in Faridabad, an industrial city 48 kilometres north of New Delhi.

They have been living in Faridabad since she was a child, but now she and her family want to move away because of the worsening air pollution.

Gupta said it is unbearable during Diwali when industrial air pollution, mixed with fireworks and stubble burning in states neighbouring Delhi, creates more trouble.

The smoke emitted from these activities during this season, from mid-October to almost the end of December, is gruelling for people like Gupta and her family.

Many people in this region move further up towards the north to states like Himachal Pradesh, where the air is relatively cleaner.

And like Gupta, those who can afford it spend most of the time escaping Delhi’s air pollution.

She said her father, who has no history of any respiratory-related disease, was diagnosed with asthma last year due to air pollution.

Gupta, who once lived in Canada but returned to her hometown in January, has also been facing some health issues.

She said the transition from living in a cleaner environment like Canada and moving to her hometown is difficult because of the air pollution.

Since returning to India, she has faced issues including nose bleeding and intensive coughing.

To breathe clean air, many Delhiites, including Gupta, have air purifiers installed in their homes as the air, even in summer, is not safe, according to the Delhi government.

Saurav Sultania, a pediatrician at Max hospital in New Delhi, is another victim of air pollution.

He said he has faced many health-related issues since moving last year to Delhi from Jaipur, about 260 kilometres southwest of the capital, including severe coughing.

Sultania said he now often feels fatigued.

Akansha Gupta, senior manager at the Indian Pollution Control Association (IPCA), a not-for-profit organization not related to Ananya, said Delhi residents could feel the issue of air pollution and its health effects.

IPCA, established in 2001 with help of the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), has been working towards finding a sustainable development solution while tackling environmental pollution.

They are working in Delhi and other parts of India, to reduce air pollution. They have been specializing in ambient and indoor air pollution.

She said many Delhi residents, like herself if they walk for five kilometres, can feel tired, lethargic, and have shortness of breath.

Pollution killed around 2.3 million people in India in 2019, according to the Lancet study on pollution and health published in May. The study said air pollution was the primary cause of 1.6 million deaths of those lost that year. About 500,000 deaths were caused by water pollution.

The Indian statistics showed most deaths were caused by ambient PM2.5 air pollution, comprised of tiny toxic particles that can infiltrate an individual’s bloodstream.

The study builds on previous research that found pollution responsible for nine million premature deaths in 2015, making it the world’s most significant environmental risk factor for disease and premature deaths.

The Lancet study found more than 90 per cent of pollution-related deaths occurred in low-income and middle-income countries like India.

Phillip Landrigan, director of the Global Pollution Observatory at Boston College and co-author of the study, claimed pollution is the most significant threat to global health and the economy.

“Preventing pollution can also slow climate change, achieving a double benefit for planetary health,” Landrigan told The Independent.

Sahil Bhandari, a professor in the faculty of applied science at the University of British Columbia, agrees with the Lancet report’s findings.

He said bringing down pollution levels is vital as both climate change and air pollution are interconnected.

Bhandari said smoke emitted from industries and vehicles, also defined as black carbon, is primarily responsible for the greenhouse gas effect and contributes to climate change.

He said many other small particulate matters from chemicals that have not yet been studied are also indirectly responsible for the climate change reaction.

“These particles are extremely damaging, we do not fully understand the mechanism by which they affect,” Bhandari said.

There are greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide and methane and other short-lived climate forces, such as chlorofluorocarbons and hydrofluorocarbon, which have substantial warming effects. Because of these, he said the earth’s temperature would rise steadily and get much warmer.

Bhandari said air pollution levels in Delhi and the National Capital Regions are much higher than the recommended WHO air quality standards and are 100 times more dangerous.

He said the health effects of air pollution are not only limited to respiratory problems but to other severe diseases that people can face further down the road, including dementia, diabetes, and walking.

Bhandari said carbon emissions from stubble burning or bursting fireworks during Diwali are short-term boosts to pollution, those emissions are hazardous.

“Those events are very short in time and extremely high in magnitude,” he said.

Bhandari said while he terms these measures as acute exposures, the most prominent health impact residents in Delhi are experiencing is chronic exposure to carbon emissions from industries, which happens throughout the year.

“This chronic exposure has been associated very strongly with mortality effects, which has a total global health impact on millions of people,” he said.

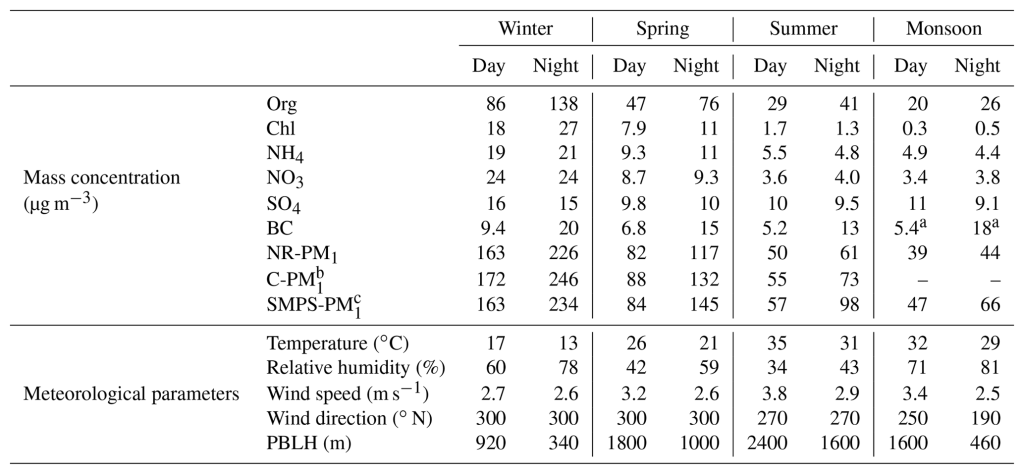

A study of submicron aerosol composition revealed that air pollution has reduced the average life expectancy in India by 1.5 years.

The study calculated emissions through different laboratory methods and people’s experiences, such as smell and odour.

The study also showed changes in wind ventilation play a significant role in the considerable seasonal and daily variation of particulate matter (PM).

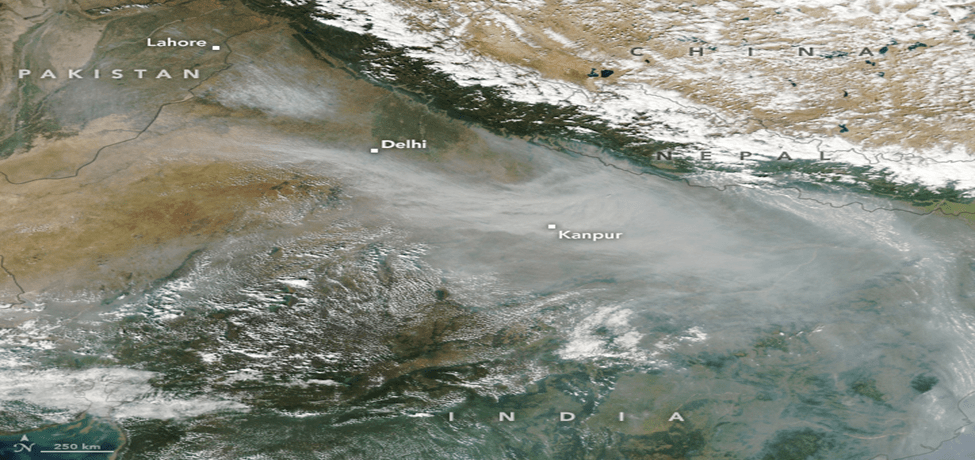

When air temperatures dip and wind speeds drop, pollutants concentrate over northern Indian cities, which lie in the shadow of the Himalayas.

The mountain range in the north forms a barrier that further blocks air movement. Indeed, unfavourable meteorological conditions also amplify primary emissions to produce spectacularly high PM2.5 concentrations.

Throughout the year in Delhi, the ventilation coefficient is at its peak during the daytime when the boundary layer height and the wind speeds reach their daily maximums.

The study claimed reducing the PM levels in Delhi will have a sizeable impact on the Indo-Gangetic plain that stretches from Sindh, Pakistan, in the west to Bangladesh in the east and the Jammu plains in the north.

Bhandari said determining emissions by each country isn’t enough. It should be calculated on a personal level. He said most of the emissions highlighted are a country’s total emissions.

“We should not just be talking about total emissions being emitted from a country but also per capita emissions,” he said.

“The reason why we focus a lot on emissions by a country is that that is how we have organized our society,” Bhandari said.

India tops the list of total emissions but in terms of per capita emissions, the developed nations account for most of the emissions in the world.

Bhandari said there is a strong need to focus on environmental injustice and start looking at other demographics, including income and wealth, which creates a huge disparity.

“The health impact is going to be different, depending on which demographic group you belong to, even within the same country,” he said.

Both the Lancet study and Bhandari highlighted a decline in deaths due to pollution associated with extreme poverty, including household air pollution.

This update in the Lancet report is based on the collected data from the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors study of 2019, which noted India has made reasonable efforts to battle the problem of household air pollution.

Government schemes like Pradhan Mantri Ujwala Yojna — which offers free gas cylinders to the poor to shift from cooking food through traditional woodfires, one cause contributing to air pollution — have made considerable efforts in the past few years.

Furthermore, the introduction of BS6 vehicle emission standards has also reduced greenhouse gas. But the problem is that the Indian government has not focused much on tackling other air pollution sources.

“India has developed instruments and regulatory powers to mitigate pollution sources, but there is no centralized system to drive pollution control efforts and achieve substantial improvements,” the report said.

Experts and residents say the Indian government’s focus on rapid economic growth is one of the reasons for pollution.

Ananya Gupta, however, blames the Indian government for most of the part for the continuing pollution crisis.

She said in the name of development, the government has cut down many trees in her vicinity.

Gupta said while critical infrastructure development is vital for India’s growth, it should not come at the expense of trees.

She said the government should be growing more trees.

Gupta told Humber News about a greenbelt area that used to be behind her neighbourhood, which was refreshing for her. When she returned to India from Canada, she saw the greenbelt was gone.

“All I can see is the concrete jungle,” Gupta said.

The protected greenbelt was cut down despite the objections from nearby residents and environmental activists, including her mother, who used to oversee the maintenance of that green area.

Her mother and other residents approached the local Member of Parliament and the Member of Legislative assembly about the issue, but they rebuffed her, saying it was a necessary step for development and public welfare.

She said after the destruction of that greenbelt, construction began on a 1,400-kilometre highway between Delhi to Mumbai.

While in the 2022 national budget, the central government allocated billions of dollars to build transport infrastructure, a mere US$3.8 million was invested in environmental welfare.

Bhandari said it is time for the Indian government to invest in controlling pollution.

It is not that they have not tried. In contrast, the government has successfully tackled the pollution related to household activities through central schemes, it also needs to focus on other areas.

“Some major sectors that have not been regulated properly at all are the industrial sectors,” Bhandari said. “These include small, medium scale, as well as large scale enterprises.”

He said in many parts of India, especially Delhi, industrial chloride is a potentially toxic chemical that has been emitted in the city and its surrounding regions.

“We need to develop new chemical models that account for these industries,” he said. The central and state government should also pay attention to increasing forest cover, which has been drastically reduced in 10 years.

Bhandari stressed the need for the developed countries to contribute too. They should contribute by reducing emissions and training local and community groups on renewable methods for conducting business.

Furthermore, the developed countries should be giving intellectual property rights to technologies through which India can create many resources to battle climate change and air pollution.

Bhandari said air pollution-related health effects are now the most significant obstacle hindering India’s public health, and it is vital to focus on them for the country’s economic progress.

“We made remarkable progress over the past few years on malnutrition, but air pollution is the biggest health impact now,” he said. “That is something we need to really think about, especially in low and middle-income countries.”